You are a man living in Naples in the 17th Century and you suspect your wife might be poisoning you. Surprisingly, this is not uncommon. Many men of your own age (late fifties) have died in mysterious circumstances, leaving their young wives, many under twenty years old, to inherit their whole estates. So what steps can you take to make sure you don’t meet the same fate?

This was the question that the Duke de Verdi in my novel The Poison Keeper was asking, and an answer I had to research. The first thing men did was always to get food and drinks tested, and so many aristocratic men employed a ‘taster’ who would try all their food an hour before it was served. This was a well-paid position and one that although dangerous was popular amongst the poor of Naples when harvests failed or they had no other way of earning a living. Naturally the ‘taster’ also kept herbal remedies nearby in case of ‘accidents.’ One of these remedies was raw charcoal, which has since been proved to be able to absorb liquid poison in the gut, and although not foolproof might give the victim more of a chance of survival.

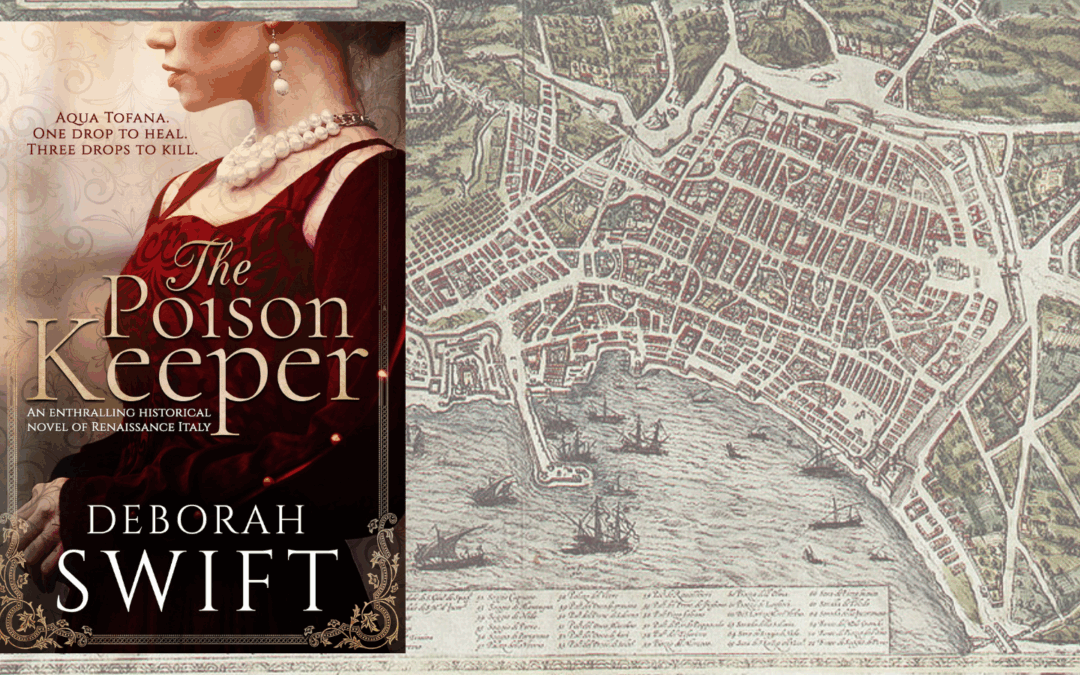

The colourless liquid Aqua Tofana, invented by Giulia Tofana in 17th Century Naples, was a slow-acting poison, and the early symptoms could appear to be a digestive problem or mild illness. The symptoms recorded suggest arsenic poisoning, and it is widely believed that arsenic and belladonna were two of the main ingredients. The first small dosage would produce cold or flu-like symptoms. But by the third dose the victim would be vomiting, and really ill and death would follow shortly after. The antidote that was common at that time was a simple digestive remedy of vinegar and lemon juice, a solution that becomes alkaline when ingested. This would have done little to counteract the effects of arsenic and belladonna, and indeed there is little one can do to protect against systemic poisoning.

|

| Bezoar Stones |

Many aristocratic men purchased Bezoar Stones which were supposed to protect against poison. Bezoars have been used for many centuries as antidotes. The stone is a solid mass like a solidified hairball found in the digestive tracts of animals, including deer, yaks, and even fish. These were often set into a jewelled or elaborate mount, and the idea was you would grind these into your food or wine and by some sort of magic it would remove the taint of poison. Sounds Bizarre? Yes, but in 1998, a study on bezoar stones proved they were effective in removing arsenic from a solution. Bezoar stones are comprised of both the mineral brushite and degraded hair. Arsenic apparently binds with the sulphur compounds found in proteins of degraded hair.

|

| Making Venice Treacle |

Venice Treacle, sometimes called Theriac, (from the Greek therion – viper) was an herbal remedy invented by Emperor Nero’s physician. It was later produced in Italy in full public view in a special ceremony, because the public wanted to be sure it wasn’t adulterated with anything that shouldn’t be there. In fact Venice Treacle consisted of more than seventy ingredients, some of which were dubious to say the least. It included benign elements like cinnamon, lavender and honey, but also included opium and even snake venom. In the 17th Century there was the idea that like could cure like. The long and complex list of ingredients made it unlikely anyone would try to make it at home, and so it became a kind of cure-all for everything from poison to the plague.

The fact that there was a lack of a definitive cure for poison meant that during Giulia Tofana’s stay in Rome over 600 men died. Whether all of them were a result of her poison, Aqua Tofana, or some died of natural causes, we will never know.