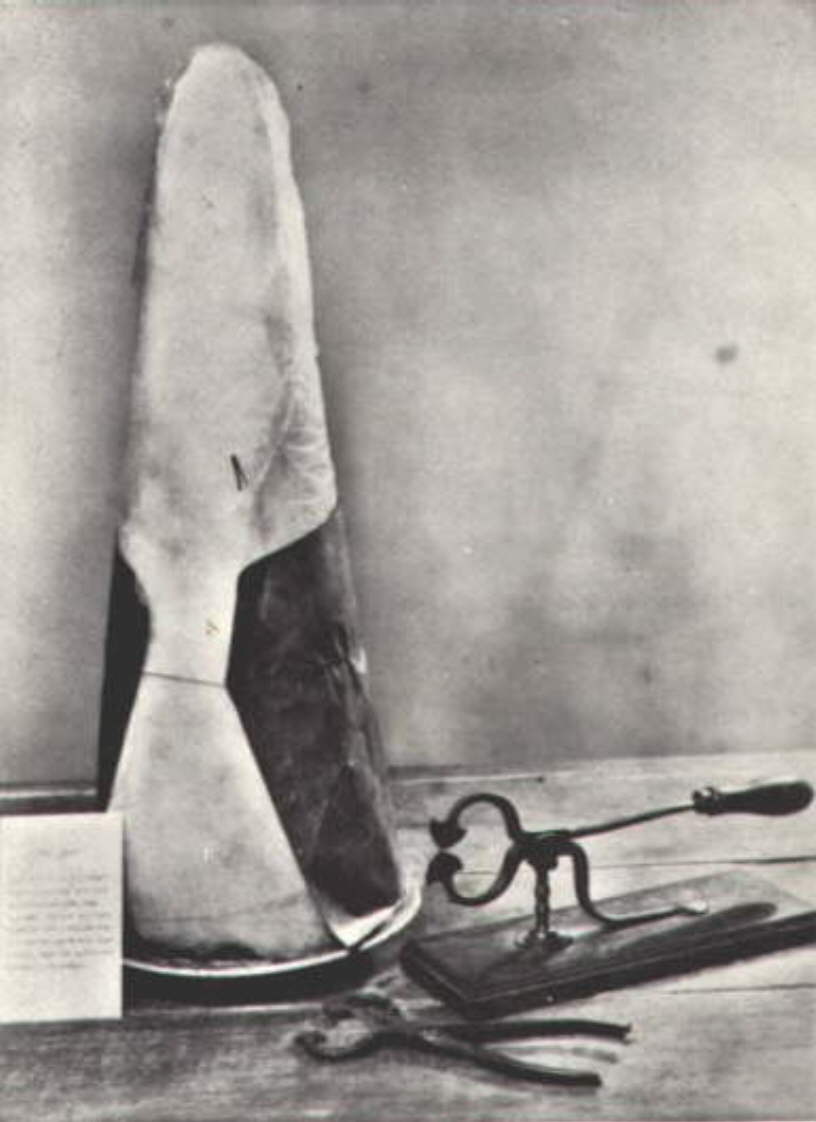

Sugar became enormously popular in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was sold in loaves and wrapped in blue paper (patented 1666) to make it appear whiter. A sugar loaf could be from 8″ to nearly 3 feet tall, but the smaller the loaf, the higher the quality and the price. Loaves were cut into usable pieces using sugar nips – iron tongs made for the purpose.

‘About the year 1544 refining of sugar was first used in England. There were but 2 sugar-houses; and the profit was little, by reason there were so many sugar bakers in Antwerp and thence better and cheaper than it could be afforded in London.’ John Stow, historian and map-maker 1720.

Sugar cane originated in Egypt where it had been grown for thousands of years, but was introduced to the New World by Christopher Columbus in 1494. But it was the Venetians, Portuguese, French & Dutch who first created a craze for sugar refining. They discovered sugar to be a lucrative import along with slaves and the ‘triangle trade’. In England, Bristol and London ships were first to go into the business in the mid 17th-century. In the North of England,

the first ‘sugar house’ in Liverpool was established in about 1673 and Liverpool’s first slave ship sailed in 1709. The town’s prosperity was built on sugar, tobacco and cotton.

Working in sugar production was a labour-intensive job. The sugar cane was was boiled and the liquid skimmed off. Moulds were then filled with hot sugar and needed to be constantly stirred for even crystallisation. After cooling for about three days, they were each stood in a collecting jar, and a clay solution added to drain through the loaves to remove the brownish colour and make them white. (ugh!) After ten days they would be more of a greyish colour and the loaves could be knocked out, and baked to remove moisture. To withstand all this, sugarhouse pottery needed to be robust. Here is how the moulds were manufactured:

From the Sugarbakers and Refiners website:

Prescot, Liverpool, 1754

In the pottery making the sugar moulds, the furnace is built in the same way as mentioned, but no Chapsels were used for the firing of the larger-size earthenware vessels. The brownish red clay is used for this purpose and is well mixed and kneaded but it is neither dispersed in water nor sieved through hair cloth. During the throwing of the large vessels a boy is also employed to furnish the motive power by winding a crank. A sugar mould, 2 feet 3 inches in height and with a capacity of 10 gallons, sells for 7 pence. A smaller one, 1 foot 6 inches in height and 9 inches in diameter at the large end, is sold for 3 pence and one of 1 foot 3 inches in height for 2½ pence. There are workers who put hoops of hazel round them as soon as they come out of the kiln. They are paid separately and get 3 pence per dozen. Moulds for Sugar Candy are made on the same way, but are closed at the top and have small holes at the sides. They are sold at the same price as the sugar moulds.

Near where I live in Kendal, the town is renowned for its ‘Mint Cake’ – a white sugary confectionery, and in Lancaster there is still a ‘sugarhouse’ visible in the town, although it is now a nightclub. The 1684 map of Lancaster shows this sugarhouse, and John Lawson, a local merchant and Quaker, built the first bridge over the mill stream to make it easier to transport sugar from his ships returning from the West Indies.

[Sugar] ‘is an excellent thing, but … fit only to be taken Physically, and not at every turn to be mixt with our common Food and Drinks, [which] forward the generation of Gout and other diseases of the Body …’ Anon (1695).

Sources:

Domestic Bygones by Jacqueline Fearn

British History Online

Sugar Girls

Sugar Refiners website

lots of refs to sugar in Southampton records, 398 chests imported by Portuguese merchant John Pyers of Viano in 1535 and by 1549 are being given as presents to important people eg 12 loaves of fine sugar weighing 30 lbs at 13d the pound given to the Duke of Somerset

Thanks for this info Cheryl. 398 chests must have weighed a bit! Love it when people chip in with more interesting facts – thanks.

Watched a BBC documentary on YouTube last year called “The Hidden Killers of the Tudor Home” and sugar was one of the silent slayers. Owing to lack of health knowledge, excess sugar damaged teeth, which in turn resulted in a high volume of dental-related deaths. Sugar: sweet but sinister.

Not much has changed then! I’ll try and find that video, Phil – sounds good.

Here’s the link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5zSyjyLAWWM

It’s a good documentary.