Description

Over-writing. It’s a sin! Historical fiction demands that we paint a vivid picture of the past. To do this, we have to tell our story, describe a world, and still bring the novel in at a reasonable length. Unnecessary adverbs and adjectives must be the first to be axed, (though now I have got to the point where very few even make it to first draft) but the surprising detail is the one that counts. The one that will stick in the mind of your reader. The reader doesn’t want to be impressed by your fancy writing skills, but rather the one true thing that will allow the imagination to conjure the rest. Your research will have a wealth of these – look for the one with the most resonance.

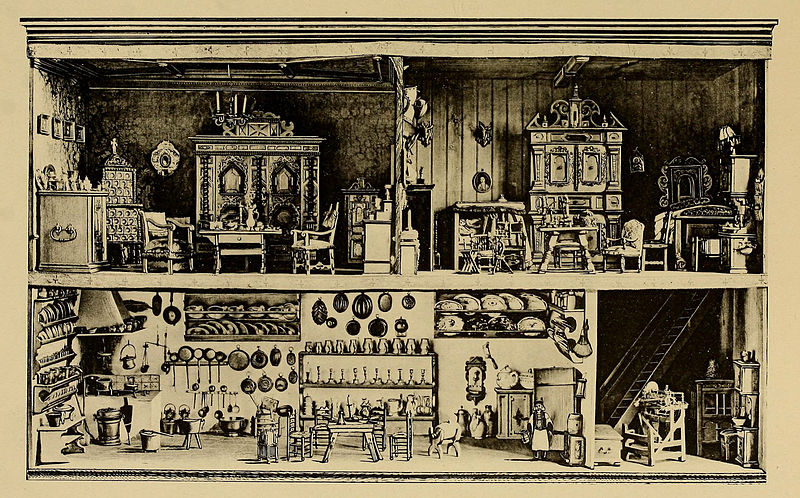

In this picture of a 17th century doll’s house, one candle is askew in the chandelier. The cupboard is one and a half times the size of a man. The jugs are ranked in size-order with the biggest in the middle. These details are much better than just stating the room was lit by chandeliers, or there was a cupboard in the corner. Specificity is the way to economy, and also the way to the reader’s imagination.

Dialogue

When I’m editing I often find I have added too much weight to character reactions in dialogue by over-writing. Assuming that I have set up my characters well, all I should have to do is leave them to talk. Not to interfere to try to help the reader.

‘He could see she was upset’.

This is a typical one – I’m telling the reader what he could see. Surely, if we know the characters well, we should know that the event (whatever it was) would make her upset and why. If he can see she’s upset, maybe he’d do something.

He reached out and took her hand.

This is much easier for the reader to imagine than ‘he could see she was upset.’ Usually, the more intense the emotion, the more taciturn the character. The dialogue should reveal everything, even if it’s restrained. The character is nearly always thinking something different to what is revealed in speech. Occasionally, it’s good to let the character start to reveal themselves, then to cut it off. Hysterical language, and verbs such as ‘gasped,’ probably indicate overwriting. It’s a long time since I’ve seen anyone gasp, (except on diving into freezing water) and I don’t suppose they gasped more often in 1616 than in 2016.

Dreams

Just don’t. The reader is still trying to make sense of the new strange world they’re in, without layering another dream world on the top. (Unless you are actually writing about Victorian Opium addiction of course.)

Good advice and it applies to every genre.

Thanks Cryssa. Though sometimes a few of these still slip into my books. I definitely have a few ‘gasps’ but trying to rein them in!