Welcome to author Jean Gill to inspire us with the ancient secrets of Welsh gold.

Welcome to author Jean Gill to inspire us with the ancient secrets of Welsh gold.

The Ancient Secrets of Welsh Gold

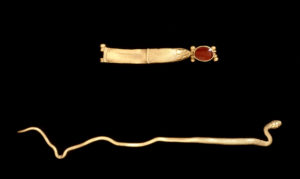

In 1824, a gold treasure hoard came to light, found in the South Wales estate of Dolaucothi. The exquisite jewellery included wheel designs on chains and snake bracelets, and was dated as 1st-2nd Century, Anglo-Roman. This led to exploration of a location that had been ignored – or shunned – for centuries, yet which held 2,000 plus years of extraordinary history.

Roman gold treasures have been found elsewhere in Britain but not beside the goldmine they came from. Dolaucothi is Wales’ – and Britain’s – only goldmine that was worked in Roman times and probably earlier. Early mining was easy, using panning and open cast methods. Then, tunnelling and deep mining followed, using the Roman engineering skills with aqueducts to flush out gold, then wheels to extract water in lower tunnel levels. Welsh gold went to the Lyons mint in Gaul to make Roman coins.

In 1153, my fictional troubadour heroes found themselves in the Welsh kingdom of Deheubarth, South Wales, which was then ruled by two brothers, Lords Rhys and Maredudd. These nomadic warrior-rulers lived in the woods during the worst attacks from the Norman marcher-lords. They must have known every inch of their homeland and they must have known of the mines.

Yet there seems to be no word of Welsh gold in medieval records. Why didn’t the men of Deheubarth seek wealth there? Lack of mining skill? Lack of interest in gold? Or superstitious beliefs about the mines?

Beside the mines is a standing stone called Pumpsaint (Five saints) with hollows in the stone where four of the saints lay their heads while the fifth went to join King Arthur. All of them await the day they rise to fight again with the once and future king. Then there is the ghost of Gweno, the girl punished for her curiosity in exploring the mines and doomed to frighten others.

I found it easy to imagine that the spirit of such a place demanded respect in medieval times and deterred looters by its very atmosphere. One person’s treasure-hunting is another person’s sacrilege, and the spirits of our ancestors haunt our imaginations in different ways; who hasn’t felt ‘bad vibes’?

I found it easy to imagine that the spirit of such a place demanded respect in medieval times and deterred looters by its very atmosphere. One person’s treasure-hunting is another person’s sacrilege, and the spirits of our ancestors haunt our imaginations in different ways; who hasn’t felt ‘bad vibes’?

Maybe, somebody in 1153 did find part of that treasure hoard.

Open at either end, each finished with a snake’s head, the bracelet was beautiful – and worth a fortune. Estela slipped her wrist into it, moved the bracelet up her arm, where it rested as if made specially for her. The diamond-shaped heads were cross-hatched in likeness of snakeskin and the small tongues had the hint of a fork, but not enough to weaken the gold.

Open at either end, each finished with a snake’s head, the bracelet was beautiful – and worth a fortune. Estela slipped her wrist into it, moved the bracelet up her arm, where it rested as if made specially for her. The diamond-shaped heads were cross-hatched in likeness of snakeskin and the small tongues had the hint of a fork, but not enough to weaken the gold.

‘It’s so beautiful.’ Estela felt like a high priestess of some ancient cult with the double-headed snake coiled round her arm. Surely such a talisman would bring magic to its bearer. She brought her arm up close to study the snake heads more closely and caught the bracelet on her cloak brooch, pricking herself against the pin.

(Extract from Song Hereafter)

Maybe, in 1153, somebody did explore the goldmines.

Dragonetz looked over the rocks beside him, down into the river valley where the mist snaked thickly, and over to the other side where the hills rose from the mist like an island, floating. He walked down, towards the caves, the tunnels and the ghosts.

The patterns of the terrain, bumpy, with trenches, told of some form of quarrying. Gemstones? wondered Dragonetz, cursing his ignorance. The signs were all here, if only he could read them.

Maybe the river was important, as it had been to his papermaking, but there was no mill here, just water and, if the square coverstone was any sign, the movement of water. Dragonetz followed the workings in the land, towards the dark holes that led into the earth.

The rainwater lay in the trenches and trickled its way like a liquid tree in ever lengthening branches. While avoiding one such pool, Dragonetz was distracted by a small pile of gravel thrown up from the churning mud, held fast by something more solid. He crouched and saw something glinting through the gravel. Not that foolish notion again he chid himself, but he scraped the gravel aside all the same, to see what lodged beneath.

What he found took his breath away.

(Extract from Song Hereafter)

Maybe, some secrets could never be told.

Whatever happened in the 12th Century remains a work of fiction and what we do know is that the late 19th Century saw the mines worked again. Gold was also discovered in North Wales, where it is still extracted today, although with difficulty and in small quantities. The Dolaucothi mines closed down in 1938, to open again years later as a top National Trust tourist attraction.

If you take the guided tour, listen carefully. You might hear the ghosts of Dragonetz and Estela, the troubadours, amid the hubbub of 2,000 years’ history. Look carefully; craftsmen skilled enough to make that jewellery must have had a workshop, and there would have been a settlement nearby, but nobody has found them yet. Welsh gold remains rare, precious and prized by modern royalty.

Song Hereafter is available as a paperback and an e-book.

Find Jean on Twitter , via her website, where you can sign up for Jean’s Newsletter for exclusive news and offers, with a free book as a welcome, or find her on her Troubadours Facebook page.

Credits: Photo of the dragon pendant in Welsh gold by Jean Gill, photos of the 1st-2nd C Gallo-Roman gold snake bracelet and necklace from the Dolaucothi hoard, courtesy of the British Museum.

Thank you for inviting me onto your blog, Deborah!